It's really satisfying to be able to read the original, handwritten, disorganized notes of old mathematicians and scientists. Finding such handwritten material is difficult: it's often only available for in-person examination in libraries, and unless you're willing to travel to make some scans of the works, you'll be in a tough spot. Even still, there's a reasonable amount of material that has been scanned, and I recommend seeking out such samples. The main purpose of this article, however, is to provide resources for actually reading old handwriting, from the 1800s back to the medieval period. And of course, I'll be focusing on everyday handwriting, and at least that used for correspondence, notes, and manuscripts.

My intention here is to emphasize points that may be unfamiliar when reading old handwriting, mostly in English, and not to provide a historical account of handwriting.

Working Backwards: Familiar Handwriting and Penmanship

Today's handwriting is mostly print, as students are required less and less to learn cursive. The lettering taught in America is a simplified, unflourished, and uninteresting system, exemplified by

New American Cursive and

D'Nealian script. Proper penmanship survives in the form of

Spencerian script, and

Palmer method, both of which are still actively learned by a small community. Other styles are more calligraphic, like round-hand, copperplate, and italic, but of course these can also be written in a less stylized fashion.

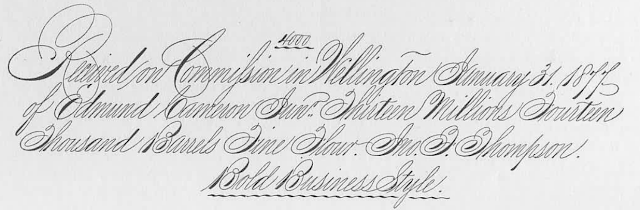

Figures 1-3. Spencerian script samples, from the New Spencerian Compendium

This sort of writing is easily read and easily understood. Similar handwriting can be found extending far back, especially in the letters and writing of the well-educated. Ben Franklin's handwriting is an example, shown below.

Figure 4. From 'Elegy on my Sister Franklin', a possibly satirical elegy originally though to be written by B. Franklin

A letter from 1861 shows some more stylistic choices. Note the letterforms for the capital 'i' (I) and the capital 'j' (J) which are highly similar.

Figure 5. A letter from 1861, obtained from the Kislak center at University of Pennsylvania

Figure 6. From the same 1861 letter. Note the abbreviation style used in Philadelphia.

Letterforms and abbreviations like this are found as far back as the Medieval period, as we'll see, although many times the penmanship is far from consistent.

More Difficulty Handwriting of the 18th and 19th Centuries

It's uncommon for handwriting to be as clear as the above. More often, you find very loose letter forms, with 'e' and 's' being reduced to hill-shaped scribbles, t's are uncrossed and are looped like L's, forms will change depending on their position in a word and the adjacent letters, and so on. We'll look at some of the details, but first, some examples.

Figure 7. Very readable letter from John Fothergill (1712-1780). Note the inclusion of the long S in the word 'express' at the beginning of the second line.

Figure 8. A more difficult letter to read, but still clear. Signed Horace Howard Furness (1833-1912)

I transcribe the letter from Furness shown in Figure 8 so the writing can be studied and learned from:

My dear Dr Fisher, will your / kindness never cease? I shall / be delighted to receive a bronze / medal (not the lighter-coloured, / nor the green) and therefor enclose / five dollars and some postage / stamps [...]

Do not, I conjure you, forget your / promise to let me see you when you / journey hitherward. I, on my part, / shall not forget your infinite kindness / to us during these last few days. / I remain, dear Dr Fisher, / Cordially yours / Horace Howard Furness

This letter serves as a good transition to more challenging script, because it includes a variety of letter forms (compare the appearance of the letter 'e' in 'therefor' and the following word 'enclose'. It also includes names (which can always pose a problem if the name isn't known), and archaic words like hitherward and conjure. The word conjure here means "implore", but it might be very difficult to decipher the word if you weren't familiar with it. This is a common issue: is the word something familiar, or misspelled, or is it an archaism?

Let's see a more difficult example, one from the history of physics: Michael Faraday.

Figure 9. Letter from M. Faraday to J. S. Muspratt. From icollector.com.

Faraday's handwriting is fairly consistent, but there are many difficult words and letter forms. For example, the capitals 'L', 'T', 'I' (capital 'i'), and 'S' all appear with nearly identical script, and the same thing occurs for lowercase letters't' (uncrossed), 'p', 'h', and 'k'. In fact, it's rather simple (if a little time-consuming) to use a program like Inkscape to trace letters so they can be analyzed for identifying marks.

Figure 10. Letter forms which can be difficult to distinguish in Faraday's handwriting. Note that the familiar lowercase 's' shape has been replaced by a loop, the lowercase 'r' can appear as a hump or a v-shape, and the letters 'u', 'v', and 'n' are nearly indistinguishable.

If you think Faraday's handwriting is difficult to read, you're not alone. When transcribing the above letter, I had to get input from three other people, and it still took multiple sittings to get some of the harder words. I'll provide the transcription here, because while this letter is a good exercise, it's only fair to give an answer key:

R Institution

My dear sir / I am sorry I cannot comply / with your note but upon principle / I never aid in the slightest degree / to any such proposition as that which / you make which has relation to / myself. I really know so little of / matters concerning my own face / that I could not tell you of / my own knowledge whether there / is any likeness of myself or not. / Lookers on are the judge & to / [theirs] I [leave it]. / Very Truly Yours / M Faraday / [J/K]. S. Muspratt

Actually, the last line is still a mystery to me, though I gave my best guess. The topmost line, 'R Institution', gave me the most trouble, and in fact I was only able to decipher it when I happened upon the words "Royal Institution" and it became obvious!

Here's another letter, which I will leave as an exercise.

Figure 11. Letter from M. Faraday.

This letter is challenging, so I can give some hints.

Hint: The letter is addressed to Faraday's friend

Magrath, and it is signed

Ever Yours.

A Sampling of Handwriting from the History of Math and Science

Below you'll find some of the handwritten texts I've collected over the years. Unfortunately, I've lost or forgotten most of the sources, so please, if you see something that looks familiar, let me know.

Augustin-Louis Cauchy

Newton

Ada of Lovelace

James Clerk Maxwell

Alessandro Volta

Medieval Writing in Secretary Hand

Medieval English manuscripts are often written in a style called secretary hand. The secretary hand alphabet can be seen in the text below.

A sample of writing is shown below:

Figure 12. Example of secretary hand handwriting, a medicinal text

The art of reading secretary hand, and the more stylistic Chancery hand, is fortunately covered in detail by a number of sources, and I'll defer the reader to them.

These are just a sampling of the available resources, and I suggest doing your own reading to get more familiar- there's a lot out there.

Comments

Post a Comment